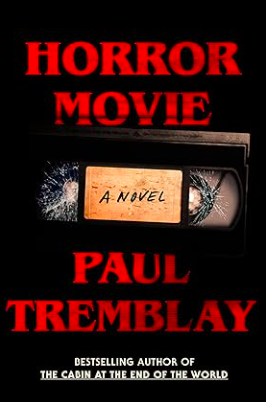

I don’t know what comes after the postmodern horror novel and, if his latest work is any indication, neither does Paul Tremblay. And that’s OK with me because Horror Movie (2024) demonstrates that–in the hands of this author at least–postmodern techniques continue to generate interesting insights. Foregrounding the artifice of narrative and the indeterminacy of truth, Tremblay’s Horror Movie forces consumers of darker content–i.e. his readers–to confront the desires that fuel their appetites and to consider their own complicity in violence. The problem for me is that his thoughtful exploration is dependent on a brutal screenplay–the script for the titular Horror Movie; and this text forms a black hole at the center of the novel, an emotional abyss in which any sense of fun sinks like a stone. Maybe I’m a fragile flower, but the screenplay’s representations of physical and psychological torture were so hard for me to get through that, in the end, I’m not sure it was worth whatever self-discoveries it may have prompted.

The book’s unnamed narrator is the last living cast member of Horror Movie, a 1993 indie film that was never completed due to an on-set death. Since 2008, when the director strategically loaded three scenes, some grainy stills, and the experimental screenplay to YouTube, the movie–if you can call it that since it was neither finished nor released–has gained cult status, garnering thousands of fans who fill every channel of social media with their speculations about its cursed origins and hidden meanings. Now, in an audiobook intended to exploit this interest and promote a reboot of Horror Movie, the narrator, who played “The Thin Kid” in 1993, reflects on the making of the film, the tragedy that ended it, and his involvement with the new project. His memoir is interleaved with the original Horror Movie screenplay, a disturbing story about three teens who torture a classmate (“The Thin Kid”) until he turns into a killer.

If you don’t enjoy torture porn, then you may struggle with the screenplay at the heart of Horror Movie. A large portion of the book–maybe even half–is dedicated to scenes in which the Thin Kid is isolated, humiliated, burned, and maimed. This isn’t the exaggerated gore of “fun” horror, the kind that stuns with exploding heads and elicits laughter with fountains of blood. Instead, the violence perpetrated against him is realistically portrayed in page after page of relentless abuse, wrought through standard instruments of torture like cigarette cherries and pruning shears. A monotonous catalog of uninspired cruelty, the screenplay didn’t leave me titillated, frightened, or contemplative. Just deeply depressed–not what I was looking for when I picked up the book. And, unfortunately, this text, interwoven as it is with the narrator’s chapters, is an inescapable part of Horror Movie’s larger project. And there is one.

Literary horror like Tremblay’s doesn’t offer gratuitous violence for its own sake; it’s always a point of departure for the exploration of larger questions. In this novel, he uses depictions of torture to interrogate the desires behind our consumption of violent content. We are continually prompted to examine ourselves by Cleo, the screenplay’s author and one of the sadistic teens in the film, who clogs the script with what is essentially Reader-Response Theory. Through parentheticals and extensions that push the boundaries of conventional formatting, she projects that filmgoers will be excited and maybe even a little embarrassed by their own barely suppressed bloodlust. As the brutality escalates, she asserts that viewers will discover their own complicity in on-screen violence and realize that they, too, are monsters, capable of inflicting pain on innocent people. It’s worth noting here that a film and a screenplay are different things; they are separate mediums that deliver distinct impressions. That said, Cleo’s expectations for the filmgoer are in no way congruent with my reaction to the text. I don’t find myself salivating with each fresh injury, nor do I identify with the attackers. This may sound incredibly naive, but I don’t think that “we’re all monsters,” and the notion that we are has been done to death in horror. Anyone who has taken a film theory class is familiar with the idea that the cinematic gaze is an instrument of violence: It’s a knife or an axe and the viewer is the one wielding it. This is an interesting metaphor, but that’s all it is. The novel’s damning equivalence between consumers of horror media and the Thin Kids attackers just doesn’t add up for me.

But is the equivalence fair if what we’re watching or reading is the product of actual suffering? In Horror Novel, Tremblay considers this more difficult question by collapsing distinctions between fiction and reality. The film industry has an ugly history of blurring these lines, particularly when it comes to low budget horror productions with egotistical male directors. In Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre–a film that Cleo admires–Marilyn Burns didn’t have to “act” like she was being hit, dragged, and cut because these things genuinely happened to her on set. Her fear and pain looked real because they were. Like Tobe Hooper, Valentina, the director in Horror Movie, has no money for stunt doubles and practical effects, nor any concern for the safety of her crew. So to get a convincing performance from the narrator, she forces him to live the part of the Thin Kid, limiting his contact with others, forbidding him to speak, and permitting him to be physically harmed. At her suggestion, he adopts a Method approach to the craft, fully immersing himself in the role until he “becomes” the character, an identification so complete that, both inside and outside of the screenplay, he has no name other than “The Thin Kid.” Through this conflation of art and life, Horror Movie suggests that our demand for fictional violence may inadvertently contribute to the real thing. If it does, then do we bear some responsibility? More concretely, when we watch The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, are we complicit in the abuse of Marilyn Burns? And is our pleasure heightened by her real pain. In other words, are we monsters?

Confusing binaries and mixing genres, Tremblay uses recognized postmodern tactics to force a reckoning between readers of horror and their consumer habits. Depending on what your habits are–for instance, do you enjoy Cannibal Holocaust and Faces of Death–this confrontation may be scary. But for me, the novel’s biggest source of chills came from the, at this point, most traditional postmodern trick in the book–the unreliable narrator with a pronounced metafictional bent. The narrator of Horror Movie hates liars but readily admits that he may be one. He openly states that his memory of events may have no relationship to what actually went down; and sometimes offers several possible scenarios to explain a single outcome. How did he lose his finger? There are two very persuasive stories to explain this and several others hinted at–you can take your pick. All of this is to foreground the blatant fictionality of his memoir, a genre that we associate with deep truths. The narrator draws the reader’s attention to the artistic choices involved in the construction of his story, imagining how he might approach certain episodes through the lens of drama or horror or some other convention. It’s clear that, through him, there is no access to what really happened, and I still find the disappearance of an agreed upon reality unsettling.

Couple this with his unnerving affect and you have the ingredients of great horror. Always oscillating between a passive introvert and a bold power player, the narrator’s personality is impossible to pin down. He has a definite edge–sometimes sheathed, sometimes exposed–and when he’s not pitiable and pathetic, he’s absolutely menacing. If there were less of the screenplay and more of him, I would have really liked Horror Movie.