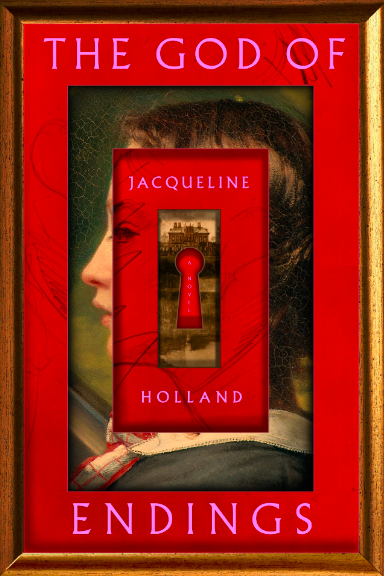

The God of Endings (2023) by Jacqueline Holland loses its momentum in the middle but makes up for it in the end.

It’s the 1830s and Anna, the daughter of a tombstone maker, struggles as her New England Village is decimated by disease. Dying of the illness that has carried away her family and friends, she is given the gift (or curse) of eternal life by her step-grandfather. He then sends her to Eastern Europe to be educated by an herbalist or witch woman, who was helpful to him in his younger days. There, Anna learns about the Slavic God of endings, Czernobog, the destroyer, who appears when you least expect it. This figure haunts her throughout the narrative.

The novel alternates between Anna as a young vampire, who witnesses the brutality of WWI in France and the ravages of poverty in Egypt, to Anna as a more sophisticated woman, living in 1984 at the height of yuppie culture. The depressed proprietor of an elite boarding school, she is preoccupied with an artistically gifted boy named Leo. Leo is shamefully neglected by his rich but selfish parents, and Anna finds herself assuming responsibility for his care. Meanwhile, interfering with her work as a teacher, Anna’s appetite for blood is increasing at an alarming rate, and she senses that she is on the precipice of a major transformation. The question of whether that change will be for better or for worse, an ending or a beginning, becomes the driving force of the story.

For someone with 150 years of life experience, Anna seems incredibly naive about human nature and makes decisions that are difficult to understand. Reading her rationalizations is frustrating and, over the course of hundreds of pages, a little boring. The book is at its best toward the end when Anna seriously considers what it means “to hit rock bottom”: Immortal life, she thinks, is miserable because it is an endless series of losses. But what if losing everything is necessary to make way for something new and better?