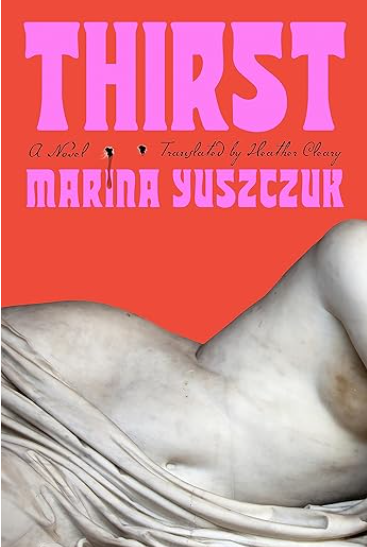

Since the 1970s, countless academic books have argued that we live in a death-denying culture and, by now, the claim is acknowledged as a truism. Still, despite the idea’s prevalence, Marina Yuszczuk’s Thirst (2024) is the only horror novel I’ve read that grapples with the modern erasure of death and the history leading up to it in a comprehensive way. This isn’t to say that the book is a dry novelization of Philip Ariès’ thesis in The Hour of Our Death. Far from it. As the book’s cover and marketing suggest, it’s incredibly sexy, at once continuing and transforming a tradition of lesbian vampires that goes back to Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla. Thirst also probes the dark corners of loneliness, motherhood, and parental ambivalence, while repurposing gothic conventions to meet contemporary needs. All of this is to say that there’s a lot going on here, and something for almost every reader. But for me, a former funeral director, the most interesting element by far is the novel’s recognition of something I’ve often thought: Vampires are the perfect vehicles for tracing the evolution of body disposal! These classic monsters leave a trail of corpses wherever they go, so it makes sense that following one, as Yuszczuk does, over the centuries would be the best way to tell a fascinating story about changing burial practices and the cultural forces underlying them. More than a history lesson, though, the novel tells a poignant story about our contemporary moment. For many of us, whether we’re dealing with aging parents or struggling with our own mortality, there is a longing to wrest death from the medical industrial complex and to reclaim this once meaningful part of human experience. Through the vampire (and an unusual bipartite narrative structure), Thirst communicates this increasingly common, albeit, unarticulated desire.

Thirst is divided into two narratives that intersect in the end. The first half of the book is told from the perspective of a centuries old female vampire who, in the early 19th century, flees persecution in Europe and travels to Buenos Aires, where she hopes it will be easier to exist undetected. In Buenos Aires, we follow the rise and fall of her fortunes as the city transforms from a muddy backwater, to a chaotic locus of disease, to an increasingly organized municipality with a modernizing police force. Fearing capture and investigation, she separates herself from the living, taking up residence in a mausoleum on the grounds of the Cementerio del Norte. Over the next decades, the rapid expansion of government administration and the advancement of forensics make it difficult for her to hunt safely until finally, in the early 20th century, she commands a cemetery attendant, whom she has befriended, to lock her in her casket.

In the second half of the novel, we meet Alma, a young woman living in present-day Buenos Aires. Alma’s struggling to process her mother’s terminal illness in a death-phobic culture, and her frustration with the silence surrounding end of life issues is beginning to take its toll. Slowly succumbing to a creeping despair, she withdraws from her young son, neglects her best friend, and disengages from work. When she receives a key to a mausoleum that her maternal line has held in secret for generations, she unlocks the casket within and frees the vampire from her century-long confinement. This mysterious creature embodies the reality of death that contemporary culture denies and Alma is at once repulsed and fascinated by her. What would happen if she were to fully embrace–both figuratively and literally–the vampire and everything that she represents?

A cursory glance of Thirst’s online reviews suggests that readers overwhelmingly prefer Alma’s narrative to that of the vampire, and I suspect it’s because the vampire is less a fully-fledged character and more of an allegorical figure, an embodiment of the novel’s broader themes. The most obvious clues to her symbolic function are that she is both nameless and, to some extent, timeless–centuries blur together for her. Moreover, she’s unable or unwilling to form affective attachments, exhibiting a kind of psychological austerity that’s a bit of a drag for readers like me who enjoy the propulsive tug generated by emotional drama. I was hoping that she would feel something for Justina, the friendly washwoman, or even Joaquin, the priest, but the only thing she feels is disappointment that, after killing them once, she can’t do it over and over again. Like a cat, she isn’t sad when her prey dies; just bored because it’s stopped moving. While I’ll admit that I find the vampire less than compelling, I also recognize that she is what she’s supposed to be: Disappointment is the wrong response to her because she’s not a failed representation of a complex conscious being. Instead, she’s a masterfully crafted metafictional device, a literary construct, without depth or motivation, who, with a wink from Yuszczuk, virtually points to her status as a textual artifact. “Nothing I do makes sense,” she says with true postmodern self-reflexivity, “I was dragged into this story; my only freedom is to create” (75). The point of her, it seems to me, isn’t to incite love, hate, or indifference on the part of the reader; it’s to personify the novels’ preoccupation with the ineluctable processes of death and decay.

And on that score, the figure of the vampire is wildly successful. She’s mesmerized by the process of putrefaction that changes her victims’ beautiful bodies into bloated masses, inflated with noxious gases and oozing the dark fluids of corruption. She revels in rot and reaches her height during the yellow fever epidemic which turns the city into a carnival of death–a chaotic pageant of the macabre over which she reigns.

Giving the queen of death–a figure who lacks the full palette of human emotions–an autobiographical voice is a risky move because the result doesn’t meet our expectations for first person narration, a mode typically used to convey the complexities of interiority. However, by taking this risk, Yuszczuk is able to give us a quasi-human perspective on the fascinating history of death practices in Buenos Aires, which closely resemble those across the cultural West; and despite its often pronounced detachment, this vantage point is still far more interesting than a dry recitation of facts. The vampire describes how, for the residents of Buenos Aires and its government officials, the march toward “civilization” means the relocation of death from densely populated centers to the margins, where it could be more easily concealed from public view. To this end, burials are moved from crowded church yards within city limits to secular cemeteries beyond them, where sentiment and capitalistic forces merge to bury death under a myriad of artistic forms. This process is already well underway when the vampire arrives in Buenos Aires in the early 1800s, but its acceleration after the yellow fever outbreak makes it increasingly difficult for her to survive.

Facing pressure from these cultural shifts, she’s forced to withdraw from society and seek shelter in a cemetery where, hidden in a crypt, the disruptive forces she represents are safely contained by images of beauty–sanitized by “the proliferation of symbols that translate death, the putrefaction of the flesh, into another language–elevated and aimed at eternity, at heaven” (125-126). The segregation and aestheticization of death dramatically reshapes her existence, at first altering her hunting habits and, finally, compelling her to go dormant in a locked casket. The stations of her journey–from a life above ground to one below–closely mirror changing attitudes towards death in Buenos Aires (and throughout the Western world), making her the perfect vehicle for this story.

As something of an allegorical figure, the vampire’s voice is qualitatively different from Alma’s, which is, well, human, with all of the psychological nuance and emotional complexity that implies. Still, their two narratives are of a piece and depend on each other for their full meaning. Most obviously, the sections have a linear relationship: Alma’s experience in the present day with her mother’s terminal illness represents a later stage in the evolution of death practices. If, during the vampire’s time, death was marginalized and beautified, today, it is virtually denied by the medical establishment, which pretends it can be endlessly deferred, and erased by the funeral industry, which inters corpses in soulless landscapes beneath flat markers–a far cry from the ornate monuments of yesteryear. Alma resents the doctors and nurses, who insist on continually propping up her mother’s rapidly failing body; and she hates her family’s inability to admit and openly discuss what’s happening. Like many people in similar situations, she longs for an authentic engagement with death, and the appearance of the vampire is in many ways a realization of this desire.

While the narratives are sequentially linked, they also have an interesting vertical relationship. The vampire’s tale feels like the latent foundation of Alma’s own, a dark and ancient substratum that’s always threatening to penetrate the light, clean surface of the world she inhabits. The reintroduction of the creature in the second half of the book represents an upwards eruption of rot–the end of all flesh, which we vehemently disavow–into the sterile atmosphere of medicalized death. And the emergence of this noxious presence feels like a breath of fresh air. Not just for Alma and those of us who regret the loss of a more death-positive culture, but for vampire fiction in general.

It’s good to once again see vampires as subversive forces in a contemporary context. These monsters have a long history and it can be difficult to dust them off, retaining the gravitas of their age while making them fresh and relevant to audiences in 2025. Yuszczuk manages to do it. In her hands, the vampire invites us to think about how we might reimagine modern death practices in a way that recenters the body and embraces the inevitable trajectory of the flesh. Maybe it’s because my parents are old and I’m aging, but this really speaks to me.