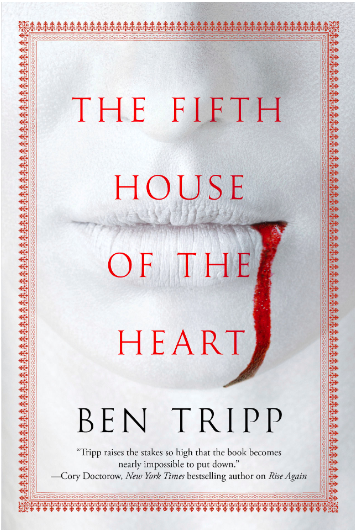

The Fifth House of the Heart (2015) by Ben Tripp should have been a series. The success of a book series hinges on a strong main character, who is compelling enough to carry a readers’ attention from one adventure to the next. Asmodeus Saxon-Tang is that kind of character. Smart, witty, and a master of understatement, “Sax” is absolutely hilarious. What I don’t find funny is Tripp’s representation of non-native English speakers. If Sax’s verbal sophistication is a source of admiration–and who wouldn’t want to have his words at their command–the other characters’ EAL (English as an Additional Language) practice of transliteration is a source of comedy; they are Sax’s foil. This is a huge blemish on what is, otherwise, a perfect book.

Asmodeus Saxon-Tang is a wealthy and successful antiques dealer, who keeps his warehouse and bank account full by robbing vampires. As immortal and highly sentimental creatures, vampires are naturally hoarders of beautiful artifacts, from Egyptian crowns to French silks. After destroying two of these creatures, Sax is set for life and ready to put vampire hunting behind him until his curiosity and insatiable greed are piqued at an auction: When he faces unusually stiff competition for a French ormolu clock, Sax wonders if his opponent in the bidding war is actually the agent of a vampire. Many vampires lost their collections during WWII and, Sax reasons, only one of these deeply nostalgic monsters would be willing to pay so much for a beautiful but not particularly valuable piece of Napoleon III bric-a-brac. By outbidding the agent, Sax has brought himself to the attention of the vampire and put everyone he knows at risk. To protect others, save himself, and–perhaps most importantly–capture the vampire’s treasure, he must travel to Europe, find the monster, and kill her. Or, really, pay someone else to do it, because, second only to his avarice, cowardice is Sax’s defining feature. With the blessings and assistance of the Vatican, Sax gathers a diverse group of mercenary vampire hunters at his French farmhouse and prepares for a final confrontation with an evil.

The novel makes interesting contributions to vampire lore. For example, the title refers to the distinctive sac or “fifth chamber” of the vampire heart which must be punctured in order to kill them. For vampire hunters, the small size of their target (not just the heart, but a special part of it) is why so many of their stakes fail to hit the mark. Another quality that, according to the novel, has helped vampires escape destruction and survive the centuries is their fluidity; they assume the species and gender of their prey, which means that they can change form by redirecting their appetites.

While I love these clever elaborations of the mythology, I also expect them from a good vampire novel and a talented writer like Tripp. What I didn’t expect were the lengthy and really enjoyable asides on other subjects. Sax is a connoisseur of fascinating people, sumptuous food, and rare objects. Offering a convincing first-hand account of the 60s bohemian scene, he drops all of the big names and seems to be acquainted with every influential figure in music, fashion and art. When he cooks for his militia of vampire hunters, he describes the food preparation in such detail that I actually recreated the recipe in my kitchen. And his exposition of the dangerous metallurgical processes behind ormolu had me going to the internet for more information on “phossy jaw.” I loved it all.

With a protagonist as nuanced as Sax, it isn’t surprising that the other characters are less developed–he’s the star, after all. But the novel really stumbles in its rendering of diverse perspectives. The vampire hunters all hail from different countries, and the vampire victim who convalesces with them at the French farmhouse is a Bollywood “item girl.” When Tripp depicts their speech, he uses transliteration. That is, the characters apply the syntactic rules from their native tongues to the English language, and this results in the patterns of error that can sometimes characterize EAL communication. All of this seems like an appropriate and realistic representation because they are not native speakers of English. But the problem is that their speech and this process of transliteration is a major source of humor in the novel. Gheorghe, the Roumanian vampire hunter, offers many examples of this kind of dialogue. On meeting the crew, his “first words” are “‘I must piss as racehorse’” (186). When asked to “keep an eye out” for an attractive vampire familiar, he responds, “I’ll keep out my pecker for her . . . You know is pecker, right? Is a word you use for the pula. The Johnson? Hahahahaha” (266). If Gheorghe is cast as a clown, so is Min Hee-Jin, a South Korean slayer. When Sax announces that he is prematurely ending the mission, she struggles to express herself and control her rage:

“You make vampire go free!” she said, composing her thought with care. . . . “it’s not my favorite idea,” he said. . . . Min threw her head around at the entire crowd, furious. Her mouth worked on foreign words that wouldn’t come. “Everybody can go fuck you!” she barked and stomped outside (309).

What’s funny here isn’t her use of “fuck,” a word common enough in horror fiction, but her malaphor: In a mistranslation, she mistakenly combines two related but different phrases: “Fuck you” and “go fuck yourself.” The comedy comes from her “foreignness” to white English speaking readers and that’s a no go.

More surprising and disappointing still is the novel’s use of EAL characters to voice racist slurs. My mouth drops when Gheorghe calls Rock, an African-American character, a “big baby jungle bunny” (309). While it is supposed to have the opposite effect, Sax’s immediate disavowal of this language–”Gheorghe . . . please don’t use racial epithets”–actually makes the scene more unsettling. Tripp uses a marginalized character to articulate racist statements that he would never put in the mouth of his hero, who immediately repudiates them. In this way, the book suggests that poor eastern europeans are bigger anti-black racists than wealthy New York elites could ever be. A character who is not American becomes a repository for America’s linguistic past and symbolizes a stage of development beyond which Sax has evolved. This kind of smugness is off-putting, to say the least.

As a horror lover, I picked up The Fifth House of the Heart for the vampires–and it delivers on bloodsucking gore–but I kept reading for Sax. At the end of the novel, he is perfectly positioned for more adventures with the undead and I was ready to join him. But, in the eight years since it was published, there has never been a sequel. Despite the problems with the book, I hope that Tripp eventually revisits Sax’s story.

Leave a Reply