You’ve got to love a horror novel that begins with an action item list, and that’s exactly what Will Maclean’s The Apparition Phase (2020) does. In the first chapter, the British narrator provides a neat inventory of what were–when he was a teen–his three favorite spirit photographs, each of which he says “will be instantly familiar . . . to anyone of a certain age.” This felt like a challenge to me, the parochial American horror fan, because, while I’m only one generation removed from him and pride myself on knowing about all things spooky, I’d never heard of these “famous” ghost images. And so, propelled by my embarrassing ignorance, I immediately googled them, backfilling the holes in my education by researching their histories. The entire novel works like this: It’s an action item list that expands your horizons by pointing you toward the best in British horror across a wide range of media. For a stateside genre obsessive like me, it’s worth reading on that account alone.

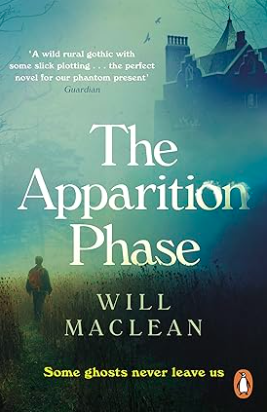

But in addition to being a great resource–a kind of transatlantic horror directory–the novel is also a triumph of literary craftsmanship. Skillfully manipulating the horror, true crime, and coming-of-age genres, Maclean is able to get the most out of his material, maximizing the impact of his story’s key elements–its stomach-dropping terror, emotional sincerity, and artistic interest. In his hands, each convention is a prism that amplifies the true colors of characters and situations, separating and displaying their strengths. I can say without hesitation that The Apparition Phase is my favorite book of the last five years.

Set in a dilapidated suburb of London in the early 1970s, The Apparition Phase tells the story of Tim and Abi, teen twins who are obsessed with all things strange and morbid. Experts on spirits, standing stones, and every odd subject in between, Tim and Abi are polymaths of the weird, and they pursue their occult studies in a private world of their own making–a gloomy goth attic–above their disapproving parents’ heads. It’s no surprise then that their first project with a new camera is to fake a ghost photograph. After showing the manipulated image to Janice Tupp, the girl collapses in class, and the twins fear that, if the cause of her swoon becomes known, they will lose their attic sanctuary forever. To keep Janice quiet, they invite her to the house and reveal how the spooky effect was created, and it’s at this point that things go terribly wrong. Rather than accepting their apology, the humiliated Janice slips into a trance and prophesizes dark futures for both Tim and Abi. Her predictions seem to be unfolding when, over a year later, Abi disappears after a chess club meeting and never returns. As his homelife deteriorates, Tim sees a psychologist who insists that he can’t move on from his sister’s abduction until he abandons his belief in the paranormal. And it’s to this end that the therapist brings Tim to Yarlings Hall, a rambling manor house, where a parapsychologist is conducting a “scientific” search for the ghost of a 17th-century warlock. Joining the group of students who have volunteered for the study, Tim encounters what seems to be a malevolent force and discovers human motivations stranger than any paranormal phenomena.

Maclean plays with the idea that words–and other material forms–are doorways to another dimension, a plane populated by supernatural entities and alternative futures that push through linguistic portals and into our world. This creepy metaphysics is illustrated by the creation scene that catalyzes the novel’s plot. For the fraudulent spirit photograph to be convincing, the figure in it “needs to live,” Abi explains to Tim; and the way to imbue it with vivacity, she argues, is with “an invocation,” a poem that will “invite it to exist.” Abi’s linguistic act was, according to Janice, a summons: both a call to the other world and a framework around which the answering negative energy could coalesce and then manifest in this one. Similarly, Janice’s lyrical prophecy makes space in the twin’s lives for a series of awful events (Abi’s abduction, Tim’s breakdown, etc.) that, before her trance, had only existed as possibilities in some mystical elsewhere. The novel’s notion of form as an inter-dimensional threshold is most clearly instantiated by Yarlings Hall. If dark verses facilitate the entrance of evil beings, then the inharmonious architecture of the mismatched manor–which is half 17th-century simplicity and half Victorian gaudiness–provides the scaffolding for the expression of pure malevolence.

In its themes and plot, The Apparition Phase is a meditation on the power of form. It’s no wonder, then, that the novel’s structure is a self-conscious (but not obnoxiously so) combination of three genres, each of which is transformed by the final product. The narrator–adult Tim–openly recognizes the artistic choices involved in representing his youth, a period that, as a lived experience, had no innate order; it is only “[r]etrospectively,” he says, that “we give our lives shape, regardless of the chaos they seem to be at the time.” Piecing the fragments of his history together, he decides to tell it as “the story of how I ended up having what I can now see was some kind of nervous breakdown.” And to some extent it is that story. A psychological collapse early in life fits neatly into the trajectory of the coming-of-age category, which typically traces a protagonist’s movement from weakness to strength, innocence to experience, rebellion to order, and so on. Yet, while Tim sets out on many of these paths, he is often diverted or blocked, never quite reaching the destinations designated by the genre. By thwarting our expectations, the novel escapes the predictability of the-coming-of-age pattern and offers something fresh, if slightly more downbeat.

This impression that Tim’s arc has been flattened, his progress checked, is strengthened by Maclean’s adoption–particularly in the middle third of the novel–of the true crime mode. True crime can feel loose and unplotted because that’s the nature of the reality it’s reporting: Murders are often unsolved and actual police investigations don’t move along at the dramatic clip of a Law and Order Episode. Sometimes the only thing for true crime writers to represent is the quiet act of waiting and the emotional fallout for survivors. And that’s the angle we get here. With no significant leads or developments in the case, the police quickly disappear from the narrative. The story then takes on a meandering quality as Tim describes the decay of his parent’s marriage, the stagnation inside his gloomy home, and the aimlessness of his days. Taking a year off from school, he wanders the industrial wasteland along the margins of his town, engaging in petty crimes like breaking locks, smashing windows, and setting trash aflame. His exploits are pointless and boring, but they’re precisely the kind of thing a teen, whose parents are checked out, might do in the aftermath of a tragedy. A year before Richard Chizmar’s groundbreaking Chasing the Boogeyman (2021), Maclean is already turning some of true crime’s most salient features to the ends of fiction.

Still, the book doesn’t sit comfortably in this genre either because, while true crime may take a detour into family trauma, it’s always focused on discovering the identity of the killer. In contrast, no one in Maclean’s novel really cares about who kidnapped Abi–it’s her absence that matters. And it’s what sets the stage for Maclean’s exploration of the idea that other worlds may be impinging on our own, speculations that are beyond the scope of true crime and the reach of Chizmar-inspired imitators, who stick to (fictionalized) cold hard facts.

To elaborate on these speculations, Maclean combines true-crime and coming-of-age conventions with those of horror, a space in which the dark fantastical regularly pushes the boundaries of realism. Here, Janice Tupp’s performance can be construed as a mix of possession and witchcraft; Tobias Salt (or whoever he is) can know things that he shouldn’t and manifest in seemingly impossible ways.

Leaning into horror, Maclean organizes the book around an eerie recurrence of themes, the most prominent of which is the uncanniness and easy corruption of twinship. Tim’s twin is replaced with a sinister shade who can only be seen by those who are tripping, psychic, or elderly. His synchronous movement with a supernatural enemy is a travesty of the natural and supportive relationship that he had with Abi. Their bond is also reflected and distorted by Sebastian and Juliet, the insular and toxic teen couple at Yarlings, who offer a sexualized and highly dysfunctional version of a brother/sister pairing. The most concrete expression of this theme is Yarlings itself. At one point, the two wings of the house mirrored each other and existed in a state of perfect architectural harmony. Now, with one side rebuilt as a Victorian monstrosity, the manor is at war with itself, its timbers almost vibrating with hostile energy. Belligerently mocking the notion of unity in duality, it’s a ghastly monument to the perversion of twinship.

Maclean also uses repetition to chilling effect by having characters pose the same question in different contexts, generating recurrences that defy the laws of mere coincidence and suggest the existence of an inexorable fate. When the reception of their spirit photograph goes awry, Tim begins to wonder if there is something wrong with him and Abi: What does it say about them that they would pull such a prank? Unrelated to their trick, this same question–”What kind of a person fakes a ghost? And why?”–becomes very important later in the novel; and the repeated framing of the query seems to short circuit time, creating a nightmarish echo chamber from which Tim cannot escape. From the vantage point of adulthood, he might put a medical (and therefore rational) gloss on his narrative by calling it the story of a “nervous breakdown,” but it’s horror all the way.

By deftly layering horror, true crime, and coming-of-age, Maclean is able to tell a tale that is at once spine tingling, emotionally honest, and aesthetically compelling. There are a few fumbles, though. The middle of the novel drags. While this may be a sophisticated kind of mimesis–Tim’s aimlessness and languor are literally felt by the reader–I couldn’t wait for him to find a purpose and rediscover his passion. Also, outside of its horror elements and on the level of basic plot construction, the book asks a lot of the reader when it comes to the suspension of disbelief. The most glaring example of this is Mr. Henshaw’s treatment method. If his objective is to discourage Tim’s fascination with the paranormal, then why would he take him to a paranormal investigation, a scenario that would only fan the flames of his enthusiasm? Asked from another angle, why would he deliver a traumatized patient, crippled by grief, to a house full of teenagers attempting to communicate with the dead? Maclean is aware that this is an implausible psychological approach and the characters openly discuss its absurdity. But he seems to have no better way to pull Tim out of his rut and into a seance room. Also, while the 1970s are notorious as a period of parental laissez-faire during which kids essentially governed themselves, I can’t help but wonder at the absolute freedom of Graham’s volunteers. That a reputable academic institution approved and funded his “experiment” strains credulity to the breaking point. Ultimately, though, it doesn’t really matter, because I would accept half a dozen improbable plot twists for the sake of this book, which is almost perfect otherwise.

While I marvel at Maclean’s deft manipulation of genre, the novel’s greatest pleasures are simpler than the kind provided by impressive formal artistry. If you are an insular American horror fan, The Apparition Phase opens the door to a new world of content. A metaphorical brown and orange VW bus, it takes you on a grand tour of 1970s televised British horror with an extended stop in 72, when the BBC aired the Dead of Night anthology, the M.R. James ghost story “A Warning to the Curious,” and–let the trumpets sound!–The Stone Tape, one of Nigel Neale’s most enduring works. For lovers of the strange and macabre who happened to live in the UK, it was a great time to be alive. And now, for the rest of us, all of these treasures are available on YouTube. When you’re through with your watchlist, there’s still so much more to explore.Tim offers a bibliography of his favorite books on British hauntings and provides a list of standing stone locations around which you could build a vacation itinerary. These granular details imbue the novel’s setting with a sense of presence and reality that is rarely achieved in the contemporary glut of nostalgic fiction. But more exciting than that, it provides a map for a multimedia experience of UK horror that–with the right resources–you could recreate today.

Having come across The Apparition Phase in 2024, four years after its original publication, I thought that I was late to the party. But now I don’t think that there was one–at least not in the United States. I’ve never seen the title in top-ten lists or heard it bandied about in bookish conversation. Still, it’s never too late to recognize an amazing novel. If you’re looking for something a little outside the well-trod paths of horror promotion, I urge you to read Maclean’s masterpiece and then recommend it to a friend.