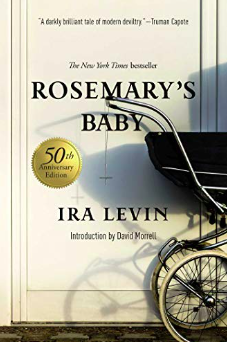

During my week off, I revisited some of the genre’s modern classics, the novels that moved horror from the moors and the gothic mansion into the city apartment or suburban home. While all of my selections were fun to read, one of them really stood out for its continued relevance: Rosemary’s Baby (1967) by Ira Levin. Levin introduces a new kind of monster with Guy Woodhouse and explores the evergreen themes of psychological violence, economic vulnerability, and capitalist consumption. While playing on a variety of contemporary anxieties, Rosemary’s Baby in 2023 reads as a clear warning to third wave feminists. Today, women are told that they can pursue a career, raise children at home, or create a role outside of these predefined options. The most important thing is that they make the choice. Rosemary’s Baby reminds us that not all choices are equal.

Levin details the breakdown of intimate communication, and his subtle investigation is more disturbing than the goriest horror action. Anyone who has ever been in a close relationship knows the significance of that look–the look of mutual understanding that passes between you and your partner on encountering an aggressive, stupid, or otherwise ridiculous person. There is an instant meeting of the minds–no words necessary. And when you go home, your bond as a couple is strengthened by replaying and ridiculing the offender’s gaffes. While performing these theatrics, your heart warms because it feels good to be immediately and completely understood by another human being. That’s how Rosemary feels when she and her husband, Guy, exit the apartment of Roman and Minnie Castevet for the first time. They smile at each other, criticize the meal, and imitate Minnie’s broad accent; with an imaginary hammer and nails, Guy mimics barring their door against the intrusive pair. But Rosemary’s glow quickly fades when her husband says in an offhand manner that he will return on the following night to hear more of Roman’s stories. This is so against her own inclinations that she immediately doubts the solidity of the common ground they supposedly share: Who is this man? she wonders. Through the depiction of a seemingly small misfire, Levin masterfully creates a creeping sense of unease that only grows as Guy becomes more mysterious.

In Guy Woodhouse, Levin has created one of the most sinister figures in the genre, and his biggest crime, to my mind at least, isn’t the one you would think. To be sure, his betrayal of Rosemary is horrible–there is nothing worse than sacrificing your wife to Satan in exchange for career gains. Nonetheless, what makes the novel so special, so memorably chilling–a classic, in other words–is the way in which he minimizes the enormity of what he has done. After only a couple of meetings with Roman, Guy agrees to the coven leader’s plan and has no second thoughts when drugging, stripping, and binding his wife for Satan’s pleasure. It’s no big deal. And the way he manipulates her after the event, continually conniving with the Castevets while dismissing the bizarre and painful side effects of her pregnancy, is unmatched in the annals of thriller/horror history. If Jack Manningham invented the art of gaslighting, Guy perfected it. He refuses to acknowledge that he has wronged Rosemary because, according to his twisted logic, no lasting harm has been done–she isn’t dead and future pregnancies are still possible. Putting his psychopathic lack of empathy on full display, he explains, “They promised me you wouldn’t be hurt . . . And you haven’t been, really. I mean, suppose you’d had a baby and lost it; wouldn’t it be the same?” (262) No, Guy, it wouldn’t. Not even close. In suggesting that these situations have equal weight, Guy demonstrates a terrifying readiness to dismiss his wife’s suffering and absolve himself of guilt.

Guy can abuse Rosemary without repercussions because of her economic dependence; and with a realism that would make any stay-at-home spouse sweat, Levin skillfully details the financial and social contexts that make her an easy target. Rosemary has given up her career and has no personal income. As her suspicion of Guy increases, she draws a clear line between her oppression and the lack of economic power afforded to her by the traditional marital scheme. She decides to “go back to work and get again that sense of independence and self-sufficiency she had been so eager to get rid of” (109). But instead of returning to paid labor, she begins the uncompensated work of reproduction. And she does so in near isolation, which is in keeping with the Casavet’s design. Like their previous victim, Terry Gionoffrio, Rosemary is estranged from her family, having only limited contact with one brother. Her father figure, Hutch, has been murdered by the coven, and her friends seem unable to offer financial support. When Rosemary considers borrowing money, one of the best sources she can name is Grace Cardiff, a virtual stranger.

Interleaving revelations of financial vulnerability with descriptions of lavish shopping sprees, Levin foregrounds the contradictions of Rosemary’s position as a homemaker. He itemizes her purchases from Saks, Tiffanys, and Gimbels, to emphasize the sheer amount of stuff that, in a capitalist society, both dictates and accompanies each stage of life: from renting an apartment to having a baby, every situation has an appropriate line of products. Rosemary’s job is to consume these products–to buy the appliances, furnishings and textiles that signify the Woodhouse’s status as an upper class couple. She doesn’t have the personal funds to see her own doctor, but Guy’s money is at her disposal when it comes to curating a comfortable and stylish home, a place befitting his role as a rapidly rising star.

Satan’s spawn poses an interesting threat to this capitalist consumption. Obviously, his black bassinet, blankets, and mitts were not purchased from the baby section of any store; these are not mass-produced products but handmade items, singular tributes to a God, crafted with love by his worshippers. So much of Rosemary’s pregnancy has been a commercial endeavor–buying the crib, wallpaper, clothes, powder, lotion, swabs, and even stationary–that I can’t help but wonder how she would provide for a baby with such a unique character and aesthetic. He breaks the machine. Moreover, shopping in the days before the internet was very much a public presentation of wealth: you browsed, touched, tried things on, etc. But how can she publically inhabit the role of mother, a position defined by openly buying and displaying infant wares, when her baby’s existence must be a secret. Guy has told their family and friends that the infant is dead, and Rosemary could walk away from the situation. Her decision to acknowledge the baby forces her into an alternative economy.

In the past decade, perhaps in response to America’s increasing conservatism, horror films and novels have revisited the occult, representing witchcraft as a weapon against the patriarchy and an instrument of female empowerment. Derived from a misogynist biological determinism, Rosemary’s authority within the coven is a direct result of her reproductive capacity: she can dictate to Roman because, as the mother of Satan’s baby, she deserves a level of deference. Like Mary worship, this isn’t particularly feminist. Still, I enjoyed revisiting Rosemary’s Baby in the context of the modern witch craze. And who knows? Maybe Satanism is the solution to capitalist excess.

Leave a Reply