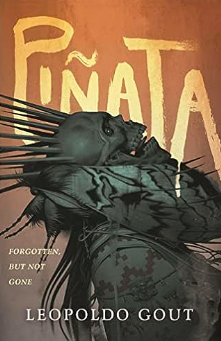

Piñata (2023) by Leopoldo Gout relocates the subject of possession from a Catholic to an Aztec cosmology. While I enjoyed this original reinterpretation of a classic horror trope, I think that the novel is at its best when examining the characters’ more mundane problems. All of them grapple with the fractures and contradictions of post-colonial identities; and it’s in the exploration of this rough psychological terrain that the book really succeeds.

An architect for an American firm, Carmen Sánchez takes her daughters, Luna and Izel, to Mexico for an ambitious work project–the renovation of a Spanish colonial abbey. Though Carmen immigrated to the United States twenty years earlier, she wants her girls to experience Mexican culture and sees the summer as a chance for them to connect with their heritage. But Luna connects with something much more sinister. When Carmen’s construction crew uncovers a pre-Hispanic piñata or tlapalxoktii, Luna is possessed by an Aztec goddess of war whose manifestation in the world signals the end times.

Forget the demons and signs of approaching apocalypse. The scariest part of Piñata is Carmen’s dread and disorientation as she navigates competing national identities. Illustrating the classic Freudian definition of the term “uncanny,” Mexico, Carmen’s native country, has become distinctly “unhomelike” (Unheimlich); she feels like a foreigner in her own land as if she were “just another American tourist” (40). She is at once afraid of cartel violence and ashamed of herself for subscribing to American stereotypes of Mexican barbarism. Yet, while she wants to dismiss sensational news reports of beheadings, femicide, and mass graves, she also can’t ignore the pictures of missing women and the impression that her daughters may not be safe. Both American and Mexican, she is psychologically ground down by the friction between these two positions and their often opposing perspectives.

This internal sense of division–a simultaneous familiarity and foreignness–carries over to the worksite where she’s supposed to be in control. Here, the men deny her link to Mexican culture, regarding her as a “gringofied expat,” and refuse to take direction from an “Architecta,” compounding her outsider status through gender-based discrimination and harassment (32). And it isn’t much better in her adopted country. In New York, she sees herself as a symbol of Mexican womanhood and regards her professional success or failure as a direct reflection on this broad group. The pressure is crushing, and Carmen’s persistent feeling of being out-of-place is as unsettling as any doomsday demon.

Other characters are also haunted by internal fractures and inconsistencies. Through Quauhtli and Yoltzi, Piñata explores the vexed relationship between the religious lives of indigenous people and the representations of shamanism produced by Hollywood. When Father Verón questions Quauhtli about his beliefs, the stone carver takes umbrage: He is offended by the priest’s assumption that his Nahua ancestry immediately qualifies him as a spiritual teacher and by the idea that complicated theologies could be condensed into an easily digestible statement of belief. Quauhtli refuses to be anyone’s “Taylor the Medicine Man” (See Poltergeist 2). And yet he has to admit that Yoltzi, a Nahua woman and a close friend, might be just the sort of person who could give Verón what he wants. For her, spirits are a part of everyday life, and, favoring simplicity over historical accuracy or nuance, she has no qualms about collapsing the different religious traditions into a single unifying narrative. This puts Quauhtli into an uncomfortable position: While he doesn’t want to dismiss genuine expressions of Nahua spirituality, he seems to suspect that these survivals are tainted by oppressive stereotypes. Yoltzi drives him nuts; but he is also respectful of her visions and, perhaps, a little envious of her easy belief.

One of the novel’s most interesting exchanges occurs when Quauhtli and Yoltzi argue over the modern meaning of ancient Aztec violence. While he believes that “[w]e can’t judge the Mexica culture by today’s standards,” she refuses to overlook or glorify a war machine: “we can’t ignore that they chose to fight, war, and invade over cooperating and harmonizing either (91).” It’s a fascinating conversation about contemporary uses of history; and, in many ways, their interactions dramatize the sifting, weighing, picking and choosing of stories that are integral to self-fashioning in the context of postcolonialism. What can and should be saved from the wreckage?

I haven’t touched on Piñata’s prodigious gore and insect horror. It’s excessive and wonderful. The problem for me is that, by the second half of the novel, these big effects begin to overwhelm the quieter, more human experiences that make the first half so compelling.

Leave a Reply