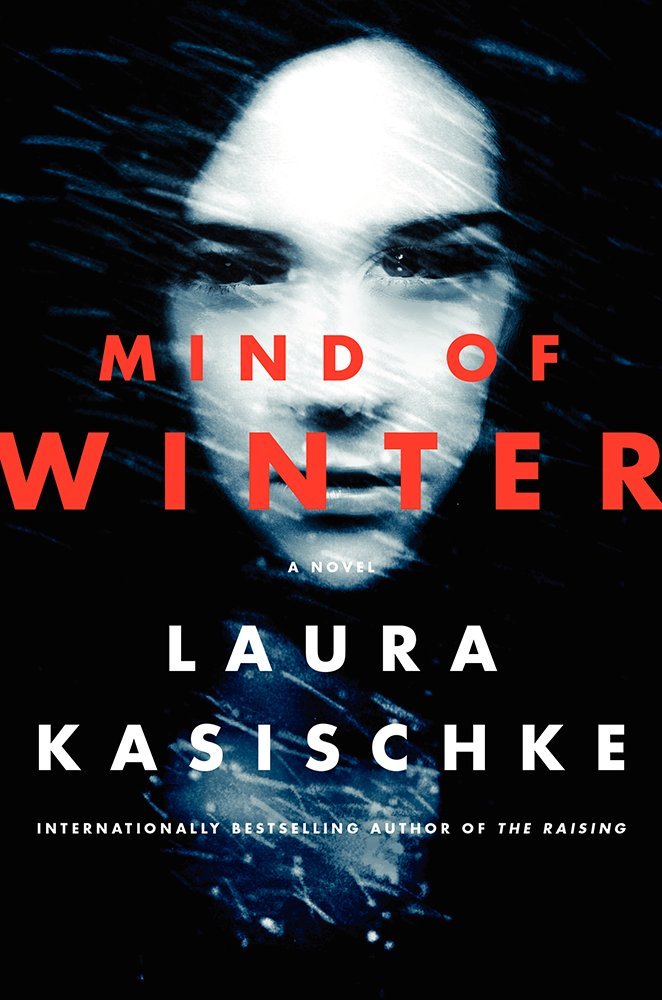

Some of the best novels bring several ideas into relationship without fully resolving their connections. Instead of the stolid sureness of a single clear note, they have the haunting musicality of a wind chime. Laura Kasischke’s Mind of Winter (2013) is a wind chime. Rather than a linear narrative with a predictably unfolding plot, it is a constellation of subjects and themes that interact in ways I could never have anticipated, leaving me in a persistent state of unease. This delicious feeling of dread is exactly why I love horror fiction and Kasischke’s novel is one of the most original I’ve read in a long time.

It’s a snowy Christmas morning in Michigan and Holly is alone with her 15-year-old adopted daughter, Tatiana. Her husband, Eric, is retrieving his parents from the airport and Holly has been left to prepare the holiday meal for their guests who will be arriving in the afternoon. With the emptiness of the house and the hours before her, Holly loses herself in the past, remembering how she and Eric came to adopt Tatiana 13 years before from the Pokrovka Orphanage #2 in Siberia. She is pulled back to the present, however, by her daughter’s strange behavior–is this normal teenage moodiness or something more? As the storm intensifies, Eric is delayed, and guests call to cancel, Tatty’s words and actions become increasingly erratic, even violent, forcing Holly to a stunning revelation.

The novel explores the interrelated emotions of regret, grief, and nostalgia. Holly used to be a poet and regrets that she can no longer write. Whether the cause of her writer’s block is a lack of talent or a lack of time due to her adopted daughter is a question she asks but is afraid to answer. She alternates between explicitly blaming Tatty–she literally couldn’t pick up a pen and write because she was holding a baby–and hating herself for being the kind of mother who would feel this way. Indeed, Holly is obsessed with what she perceives as her faults, flaws, and sins. For example, she can’t forgive herself for not bringing toys to Tatty at the orphanage and gifts to the nurses in charge of her care. Mired in regret, she is also consumed by grief. Even her writing, when she was able to write, was purely elegiac. Prior to the adoption, she had a grant to write a book called Ghost Country, a memorial tribute in verse to her lost ovaries. Holly’s ovaries were removed to save her from the BRKA1 genetic mutation that killed her mother. All of her memories seem to orbit this original loss and her seeming inability to mourn the women in her family (her sister later died of the same disease) underscores an emotional numbness in Holly; she seems to have cultivated the “mind of winter” described in Wallace Stephens’ poem. Her most salient emotion is nostalgia for a conservative past–a time when you could carry your meat in unrecyclable plastic bags, spray deadly pesticides, and refuse vaccines for your child without being judged by society.

All of Holly’s tendencies–toward regret, grief, and nostalgia–are elegiac; they compel her to turn away from the present and toward the past, to obsessively ruminate on other times and places. Her elegiac posture prevents her from objectively seeing Tatiana and understanding her needs, which is what ultimately leads to the novel’s horrifying conclusion.

Kasischke signals her novel’s “literariness” through her choice of title and supports the connection with inventive imagery and smart stylistic choices. In her meditative circling, Holly moves from the increasing preference for ethically raised food, to the blank expression of her mother in a casket, to the fortunes of her family’s chickens. Is it, she asks, the soul’s goal to be cage free? Like Holly, I have backyard hens, but I have never thought of this. Kasischke defamiliarizes the most ordinary things, forcing us to think about them in new ways, and that is the hallmark of poetry.

Moreover, her decision to tell the story in third person shows a deep understanding of the relationship between narrative voice and reader response. This novel could very easily have been written in first person with Holly relaying every nuance of her consciousness. It would then make sense that she doesn’t know what Tatiana is thinking–after all, no one really knows what’s going on in someone else’s head. However, a third person narrator is often omniscient–they have access to everyone’s thoughts and can share them with the reader. What makes Kasischke’s use of this mode so interesting is that, while Holly is entirely transparent to her narrator, who provides a detailed topographical map of her moods, Tatiana is an impenetrable mystery, not only to her mother, but to the narrator and, therefore, to us. She is unknowable to a rhetorical perspective that should be all-knowing, a blindspot from a position that should offer a perfect view–and this is what makes her terrifying.

While a big “secret” is revealed at the end of the book, Laura Kasischke’s Mind of Winter is no one trick pony; in fact, it’s the kind of novel that benefits from an archaeological approach–you unearth more with every pass. In short, it is literary horror at its finest.

Leave a Reply