H.P. Lovecraft and I have something in common: We are both from Rhode Island. And while he hails from Providence and I am from a rural backwater, when you live in a state that’s a 30 minute drive from end-to-end, everyone is your neighbor. Since my neighbor was a wizard of the weird tale and a horror icon you would think that I, lover of all things grim and ghastly, would be a master of his oeuvre. But the fact is that I am just getting acquainted with Lovecraft. For decades, I avoided his work because I mistakenly thought that it was science fiction, and space opera isn’t my thing. As a teenager haunting Thayer Street, a hipster thoroughfare adjacent to Brown University, I saw the image of Cthulhu on t-shirts and telephone poles but found the tentacled creature more ridiculous than scary. Mostly, I was intimidated by Lovecraft fandom, the pilgrims who visited Swan Point Cemetery and quoted tales like prayer. I like my writers, but I don’t worship them; and this kind of memorization often functions as an exclusionary practice, intended to separate the men from the boys (and in the 90s, Lovecraft fandom was most definitely a boy’s club).

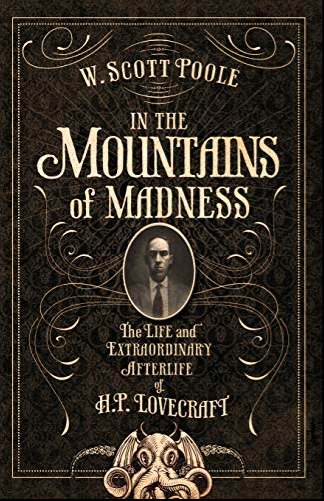

What finally prompted me to take up Lovecraft was Stephen King’s Danse Macabre. In his friendly and accessible way, King convinced me that a knowledge of Lovecraft would only enrich my appreciation for horror in general, and he was right–it has. Also, Lovecraft has satisfied an aesthetic desire that I didn’t know I had: When I read horror, I want an evocative thicket of adjectives and not an austere Hemingwayesque sentence. But now that I have read some of Lovecraft’s essential works–”The Call of Cthulhu,”The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” and “The Color Out of Space,” I want to know more about the man who created them and the context in which they were produced. I found the perfect resource in W. Scott Poole’s In the Mountains of Madness: The Life and Extraordinary Afterlife of H.P. Lovecraft. While this biography would be a rewarding read for even the most hardcore Lovecraft fan, it is especially suited for readers like me–those who do not yet have a Cthulhu tattoo.

There are many things to recommend this book to the Lovecraft novice. First, Poole tells you what you’ve missed. He sketches the history of Lovecraft biography and scholarship, introducing all of the major players from August Derleth, who invented and perpetuated a limiting image of the author, to S.T. Joshi, the undisputed authority on Lovecraft, who professionalized the field of study. After introducing the key figures and outlining the conversation, he makes several critical interventions that might interest a newer, more diverse, readership. My favorite is his reevaluation of the women in Lovecraft’s life. Poole makes the case that without his mother’s indulgent parenting style, his grandmother’s study of astronomy, and his aunt’s chemistry books, Lovecraft’s peculiar thematic obsessions would not have coalesced. Pursuing interests typically associated with men, these women gave Lovecraft the tools that he needed to combine science, technology, and the occult in his own signature style. Poole also locates Lovecraft at the root of modern day nerd culture. He explores the author’s connection to the structure of internet forums, the dynamism of role playing games, and the transformation of eccentricity into a positive trait in white middle-class culture.

Perhaps Poole’s most significant contribution to Lovecraft scholarship is his discussion of race. To say that Lovecraft was simply a product of his time in his espousal of racist and antisemitic views is inadequate because, as Poole shows, there were alternative viewpoints readily available to him. Indeed, progressive ideas were often articulated by his core group of friends. In other words, Lovecraft’s hatred was a conscious choice. And it leaves a complicated legacy for the many writers of color who work in the genre. Poole considers how the horror/sci-fi community has attempted to acknowledge Lovecraft’s racism without completely rejecting him and jettisoning his beloved creations.

Poole believes, and I agree, that one of the best ways to engage with Lovecraft’s vexed history is to confront his work. He wants you to put aside the endlessly proliferating commodities that have turned Lovecraft into a brand, a collection of signs signaling white hipsterism, and actually read the tales. To make this prospect less daunting–and with so much to choose from, it can be challenging to find an appropriate entry point–he has grouped the stories into categories, curating collections for Neophytes, Adepts, and Cultists. His suggestions have helped me chart a course into the eldritch wilderness of Lovecraft’s writings, and I am grateful for the guidance. If you are a Neophyte like me, this biography will initiate you into the unspeakable mysteries of Lovecraftian arcana; and if you are a Cultist, it will give you a fresh perspective on familiar nightmares.