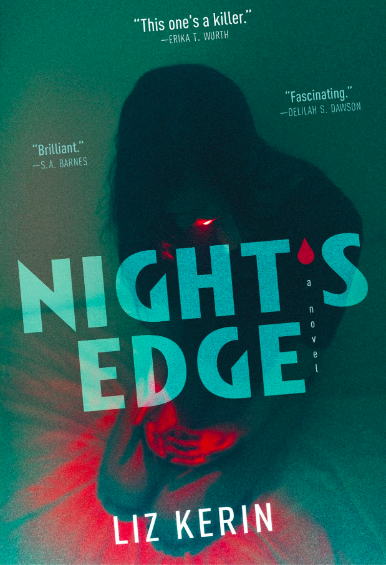

Vampires have always been a device for probing cultural anxieties, and this tradition continues in Liz Kerin’s Night’s Edge (2023). Exploring pandemic paranoia, domestic abuse, and political violence, the novel uses bloodsuckers to exacerbate social problems and expose their dynamics. It’s clear and insightful but also depressing. Night’s Edge is like the music of Radiohead: While it’s undoubtedly good, it also brings me down. Your tolerance for dark subjects will determine whether or not you enjoy this solid addition to the vampire genre.

When Mia was 10 years old, her mother Izzy, contracted Saratov’s Syndrome–the medically sanitized name for vampirism–from her abusive boyfriend, Devon. Since then, the syndrome has become a pandemic, forcing government agencies to impose curfews and lockdowns and to develop new technologies: blood scanners that inhibit the mobility of the infected and slow the spread of the virus. Despite the subsequent loosening of pandemic protocols, Mia, who is now 23, will never escape the constant and crippling state of lockdown that she and her mother have created in order to stay together. For 13 years, they have kept Izzy out of the forced treatment facilities known as “Sara Centers” by following a strict set of rules: No friends, no dating, and no life outside of each other. However, with Devon’s sudden return and Mia’s burgeoning sexuality, their private prison is about to blow open.

Night’s Edge enhances the grimness of reality and then forces you to stew in it for a few hundred pages. Instead of allowing victims (and readers) to transcend the human condition, Kerin’s vampirism exacerbates familiar problems, tipping every bad situation into a worst case scenario. Covid is a serious respiratory illness, but it’s nothing compared to what Mia faces. Imagine it: If exposure meant certain death and a tedious afterlife as a bloodsucking corpse, preventative measures would be taken very seriously; and the primal fear of physical attack would dwarf the low hum of our erstwhile pandemic dread. Vampirism not only intensifies the response to contagion, but it also amplifies domestic violence. Combining superhuman strength and speed with bestial pheromones and cunning, Izzy can physically harm and emotionally manipulate her daughter in ways that a human abuser could not.

Mia’s home life is relentlessly bleak and, so, too, is the rapidly changing political scene outside her door. A grungy demagogue, Devon uses charisma, fiery rhetoric, and social media to organize the infected under the banner of their disease. He argues that Saras are more highly evolved than humans and urges them to embrace their killer instincts. Ordinary identity politics are raised to the level of a blood sport when “living authentically” means hunting and murdering those outside of your group. Right now, I can’t stomach even fictive representations of cult-like loyalty to a dangerous charlatan; they’re too close to reality to be entertaining.

In Night’s Edge, vampirism actualizes the explosive potential of dangerous situations. But more than just an accelerant on a fire, the novel’s monsters are interesting in their own right. I like the story of their origins in Russia and appreciate that they exhibit the conventional features: sharp teeth, bloodless pallor, amazing strength, feline agility, and so on. Moreover, the old mythology gets some interesting updates: the usual list of vampire foibles now includes coffee and rust. In Mia’s world, drinking Starbucks is a safety measure, and it’s fun details like this that kept me going.

Whether through nostalgia, gore, or unintentional horror, all of the vampire novels I’ve reviewed here have offered escapism. Night’s Edge breaks that trend with a sledgehammer. Ultimately, this review says more about me than it does about the book. Reading horror for pleasure, I don’t particularly enjoy dystopian mashups of the news or realistic depictions of abuse. So while this is a great novel–relevant, thoughtful, and well-written–I am not the right audience.

Leave a Reply