Review by guest commentator VamPullet

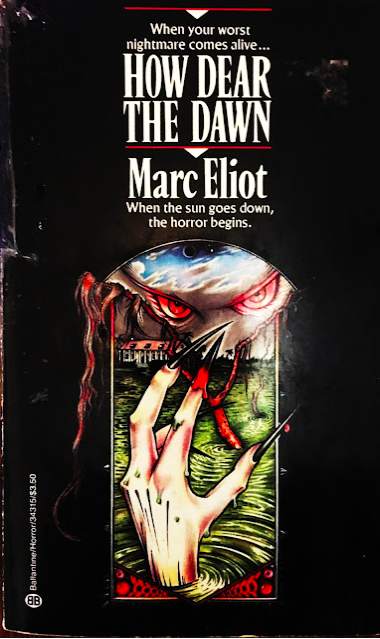

In How Dear the Dawn (1987) by Dave Pedneau (aka Marc Eliot), a slaveholding vampire from the Antebellum South terrorizes a beach town. While this sounds like a mashup of Interview with the Vampire and The Lost Boys, it isn’t nearly as good as either one of these works. Still, bloodsuckers on the boardwalk are in keeping with the season–it’s time for a light summer read. And while the setting is fun and the gore stunning, the book also clumsily gestures in more serious directions. Pedneau is preoccupied with comparative mythologies of the vampire, spending ample time on the overlap between African and European stories of the undead. If, like many readers of Anne Rice, you are interested in representations of race in vampire fiction, How Dear The Dawn can be a rewarding read.

An old beachcomber hauls a sunken casket to shore and unleashes a vampire on the tourist town of Twilight Beach. When the vampire’s first victim, Jo Ann McGhee, misses work, her best friend, Alexas Nolan, tries to convince Deputy Mark Travis that something is seriously wrong. Travis’ scepticism quickly turns to fear as he struggles to understand and contain a wave of seemingly supernatural crimes. Jo Ann’s disappearance is just the first in a series of strange occurrences in Chicora County: The police discover mutilated bodies drained of blood and hear reports of creatures with glowing red eyes. While morgue attendants claim that the dead can walk, sick residents lack the strength to rise from their beds.

Convinced that something evil is afoot, Father Dobree, a local priest who struggles with alcoholism, consults Gabe, a backwoods centenarian and voodoo practitioner who can “read the signs.” From Gabe, Dobree learns that Sterg LeVeau, an Antebellum Era vampire, has returned from his watery grave to drain the living dry. With the bodies piling up and Alexis in danger, Travis begins to believe Dobree, but can he convince Det. Sgt. Jim Cramer and the rest of the force before it is too late?

Like Santa Carla in The Lost Boys, Twilight Beach is the ideal setting for a tale of vampirism. The Lost Boys was filmed in Santa Cruz, a city in California where skate punk, beach boho, and academic culture (it hosts UCSC) mix and mingle, creating a scene that is lightning in a bottle. The Lost Boys exploits this ineffable cool through endless shots of the boardwalk on which tattooed and pierced bodies display themselves for voyeuristic (and ultimately vampiric) consumption. While Twilight Beach, a small vacation spot in South Carolina, can’t compete with this hipness, it still shares the features that make Santa Clara the preferred home of David and his crew. For instance, Twilight Beach’s population is transient, made up primarily of tourists and the workers who come for the summer to support them. When people are on holiday or just passing through, they tend, Pedneau stresses, to indulge in excess–drinking, taking drugs, or engaging in unusual sexual encounters. So if someone disappears, it could be dismissed by a lazy beach cop as a consequence of their own illicit or extreme behavior. In other words, if you’re a vampire, you can feed with impunity.

Not only are beach towns perfect hunting grounds, but they have a deliciously creepy feel that your average residential neighborhood, with its familiar streets and faces, can’t match. That’s because when a place is home to no one, it feels empty and heartless even at peak season. A character in its own right, the beach town adds a dark depth to these stories that would be missing in any other setting.

While the setting of Pedneau’s novel reminds me of The Lost Boys, the character of LeVeau is strongly reminiscent of Anne Rice’s creations Lestat and Louis. Returning to the Early Republic in Interview with the Vampire and the Antebellum South in How Dear the Dawn, both novels depict the horrors of chattel slavery and suggest the survival of African cultural practices in the South. Like Louis and Lestat, LeVeau is from Louisiana, owns a plantation, and lives off of enslaved Africans. All three face a slave rebellion but, while Louis and Lestat escape, LeVeau is sealed in his casket and submerged in Chicora Inlet’s salt water, which strips him of his power. This salt water trick comes from African tradition, according to Gabe, who, functioning as a point of cultural transmission, tries to teach Father Dobree what his mother taught him. In a heated debate with Dobree, Gabe insists that LeVeau is a zombie, while the priest argues that “zombie” and “vampire” are two words for the same thing.

Clearly intrigued by comparative mythology, Pedneau considers how the persistence of African folkways might shape and change European conceptions of the vampire. His approach to race is often cringeworthy: The idea that African Americans are closer to nature and more spiritual is a tired, racist trope; and the rendering of Gabe’s speech is awful. Nonetheless, Pedneau’s explorations of linguistic and cultural differences add interest to a novel that, in other ways, feels like a basic police procedural.

From what I’ve written so far, you might get the impression that LeVeau is cool like the vampires in The Lost Boys or sophisticated like Lestat. He’s actually a total buffoon and his ineptitude is the best part of the book. LeVeau’s first convert, Jo Ann McGee, openly defies him and he’s flummoxed by her intractability. Like an overwhelmed parent, he rings his hands and delivers empty threats of a future punishment. Kids today. In addition to being weak, his clothes look like they’re from a stage play and his breath is foul. Bad breath in a vampire isn’t unusual–they drink blood, after all. But Pedneau mentions the odor so often, that the phrase “stench of putrefaction” could be the trigger phrase in a drinking game. It’s compared to rotting fish, an open grave, and the list goes on. With so many strong and sexy vampires out there, it’s refreshing to find one who’s a fool in need of a breath mint.

If you’re not grossed out by LeVeau’s mouth, there are undoubtedly other descriptions in the novel that will repulse you. I consider this a solid point in the book’s favor. Depictions of nausea beget nausea, and there are countless instances of police officers gagging, coughing up bile, and full-on vomiting. They get sick for good reason: The gore in this book is glorious! Heads slowly blacken and swell with putrescent gas or suddenly explode like “overripe tomatoes.” At the height of the blood orgy, LeVeau detaches his rotting arm and, after swinging the appendage overhead to maximize velocity, pitches it at an officer, who is then choked by its still animated hand. The carnage is endless and amazing.

Whether you’re seeking beachtime relaxation, inventive descriptions of decapitation, or cross-cultural approaches to vampire mythology, How Dear the Dawn has it all.

Leave a Reply