As a reader of horror, I rarely encounter tales of time travel and its effects on subjectivity, topics typically reserved for science fiction and fantasy. While I usually steer clear of these genres–just my preference and not a pronouncement on their quality–I suspect that I might enjoy them if their tropes were stripped of techno aesthetics and disentangled from the rules of overbuilt worlds. And that’s exactly what Lisa Tuttle does in her novella My Death (2004). Interpreting temporal loops and bizarre models of selfhood through the lens of folk horror, she crafts a deeply unsettling book that combines space/time glitches with Pagan gods and cursed islands. Tuttle adds an almost cosmic dimension to horror’s favorite climactic reveal–the self-deceiving protagonist–and communicates the dizzying sense of a circular self through the brilliant use of metafictional techniques. To be sure, there’s a lot more going on in this text than a display of postmodern cleverness and a repurposing of another genre’s elements. She also considers the experience of grief, the erasure of women artists, and the consumption of sexually explicit images. It’s her intimate and insightful exploration of these themes that initially prompted my investment in the book’s narrator. But by the end of My Death, I had left the familiar ground of these feminist concerns to enter what, for me, is new and exciting territory, a space between categories where shiny speculative gambits assume a darker hue. So if you, too, are a sci-fi-phobe but want to explore some of its traditional concepts, then check out My Death.

In My Death, the narrator, who remains unnamed throughout, is an American expat and author living in Scotland. Since the death of her husband a year and a half before, she has been unable to write and is now anxious to get her career back on track with a biography of Helen Elizabeth Ralston. Herself an American expat and writer, Ralston is remembered–if at all–as the “muse” of painter W.E. Logan and the only witness to an incident that changed his life. When the couple visited a small island off the coast of Argyll, Logan was mysteriously blinded; and Ralston, after sailing him back to the mainland, immediately left Scotland for Paris, never speaking to him again. Logan’s sudden and inexplicable blinding radically altered his artistic trajectory, transforming him from an unremarkable society portrait painter into the author of visionary books on Pagan gods. While his career was revitalized and his productions celebrated, Ralston’s work was largely forgotten. Hoping to rectify this gap in the historical record, the narrator frames her proposed biography as a reclamation of a lost female artist in the modernist tradition. But this ordinary research project takes a surreal turn when she interviews the 96-year-old Ralston, who describes dreams and memories that are uncannily similar to her own. How, she asks herself, can such personal and seemingly unique experiences be shared? As more improbable congruities emerge, the narrator wonders if she is a dupe–the victim of a conspiracy–or an unconscious partner in a relationship with herself that defies space and time.

My Death offers an original take on one of the most commonly used twists in horror: The self-deceiving protagonist. Whether suffering from split personality disorder or unconsciously reenacting repressed trauma–and remember, I’m using the faux psychology specific to horror–the sunny main characters of works that rely on this trope have no access to the darker parts of their psyches, which are like dank basements inhabited by sinister shadow selves. And so, when the cellar door is left ajar, they unknowingly commit ghastly crimes and only return to themselves after the fact. We’re all familiar with scenes in which the protagonist, surrounded by bodies, looks down in amazement at his or her bloodied hands and realizes that the killer is within. What makes Tuttle’s novella terrifying isn’t that the narrator has a murderous alternative persona–far from it–but that her “self” is structured in such a wholly unexpected way. I tried to correlate its contours and workings with the pop culture conception of reincarnation–the interpretive framework that probably comes closest to the version of selfhood described by Tuttle. But while the transmigration of souls can account for some of its aspects, many more remain unexplained. What’s happening to the narrator is much weirder than a past life recollection or a restless subconscious mind. Her experience suggests a self with a truly alien configuration–one (and, yet, not quite one) that seems to transcend the material world while bound to specific physical bodies; that simultaneously exists in different forms but with selective awareness. The very possibility of this mode of being unnerves me far more than the standard mental schism afflicting so many characters in horror.

I suspect that modified hive minds (at once shared and compartmentalized) are not uncommon in sci-fi and fantasy, whose readers probably have a better vocabulary than I do to discuss it; and I know–albeit through hearsay–that time travel, another major element of My Death, is a favored subject in those genres. As my hedging suggests, I am woefully ignorant in these literatures. If I were conversant in them and their tropes, it’s possible that my approach to the weirder components of Tuttle’s book would be better informed and my impressions of them more articulately presented. But maybe not. And that’s because, while Tuttle is known for sci-fi and fantasy, she’s clearly accommodating her horror fans with this one.

I love My Death because it packages the sci-fi theme of time travel in the wrappings of horror, making it accessible to people like me who avoid books with complicated worldbuilding or detailed descriptions of speculative technologies. I get to play with the idea of temporal loops without having to learn about Tardis’ (Tardi?) or other forms of space gadgetry. What Tuttle describes here is much more basic and even primal. Instead of being the product of cutting edge human efforts–intricate machinery and Hawking-level physics–the wormhole (for lack of a better term) in My Death seems to be an ancient feature of a desolate island, which may or may not be the embodiment of a powerful Pagan Goddess. Whether the time loop is an expression of a deity–a special talent tied to a primeval force and its land–is never spelled out. But it’s implied, and that’s enough to situate this typically sci-fi phenomenon firmly in the territory of folk horror, where I was thrilled to discover it.

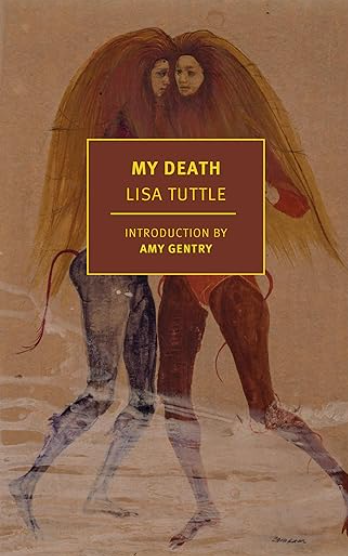

The circularity–both of time and of lives–is a central theme in My Death, and it’s reflected in its metafictional style, the processing of which left me feeling appropriately disoriented. As Amy Gentry points out in the novella’s introduction, there’s significant overlap between the lives of Tuttle, the narrator, and Ralston: All three are American expat authors; moreover, like Tuttle, the narrator writes science fiction and has lived in Scotland since the 1980s. For me, this layering created a sense of genre slippage in which I was constantly and unintentionally shifting my relationship to the text, approaching it first as fiction and then autobiography. And then back again. Faced with a detail about the narrator or Ralston, I would experience a sense of deja vu–did I already read this in Gentry’s bio of Tuttle or in relation to some other character? Of course,Tuttle couldn’t anticipate what her readers would know about her, and so part of this is probably unintentional. But what is intentional and an effective device for aligning the narrator’s and reader’s experiences is Tuttle’s figuring of the book into its own narrative. My Death is ostensibly the narrator’s autobiography, but it is also represented as an externally produced object that she stumbles upon and describes in great detail–from its binding to its plot. The book becomes an agent that acts upon the narrator and ultimately determines the course of the story. While I often find this kind of postmodern self-reflexivity overwrought and distracting, here, it totally works. For two reasons: Firstly, the temporally vexing status of the text isn’t apparent until the final chapters which means that I didn’t have time to tie myself into knots over it; and secondly, it creates a delicious Sixth Sense-like twist.

Like that movie, My Death begins by leading you in one direction, and ends up taking you somewhere else entirely. At first I was focusing on three paths: the narrator getting her life back on track, the historical forgetting of women artists, and even the reception of difficult works of art. But while all of these topics are launched, they never take flight into full stories; they’re not what the book is really about. Transcending grief, misogyny, and even art, its true subject is the narrator’s self-discovery: the awful sublimity of her realization that, at a profound level, she is not who she thinks she is.