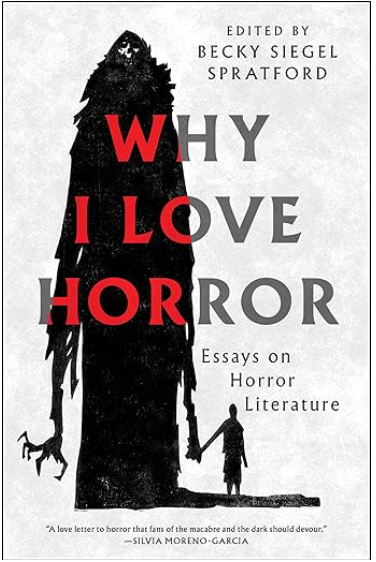

Let’s talk about Grady Hendrix’s deeply strange contribution to Why I Love Horror: Essays on Horror Literature (2025), edited by librarian and Readers’ Advisory specialist, Becky Siegel Spratford. The anthology collects essays from eighteen of the genre’s biggest names—writers like John Langan, Tananarive Due, Paul Tremblay, and Victor LaValle—each reflecting on the fears, influences, and experiences that shaped their work. But one of these things is not like the others. Hendrix’s piece stands out because, in it, he suggests that his father—a cardiologist also named Grady Hendrix—was a serial killer. Wait, what? You read that right. What Hendrix is doing isn’t quite memoir and it isn’t quite fiction. It’s autofiction let loose in the realm of horror. There’s precedent for this in the work of Richard Chizmar and Bret Easton Ellis. But Hendrix foregrounds—more than either of them—how the merger of autobiography and horror raises the ethical stakes inherent in transforming “real life” into genre narrative. This collapse of ontological distinctions has the desired effect: his use of a sensational horror trope to explore what I’m guessing was a difficult relationship is certainly disturbing. But given the potential ethical risks, I’m not sure it’s the kind of disturbance the genre needs.

When we come to Hendrix’s essay, we expect memoir, not fiction, an assumption encouraged by both its publication context and editorial framing. Why I Love Horror isn’t a novel or a short story collection; it’s an anthology in which the authors revisit formative memories and important incidents in their lives. Brian Keene describes his childhood in rural Pennsylvania in the turbulent 1970s. Alma Katsu talks about her work documenting genocide for the U.S. government. (Sure, some of the writers dip into the fantastical: Did John Langan really hear a Sasquatch knocking on a tree? Is Josh Malerman’s man on the train real? Probably not, but it doesn’t matter. Their playful winks are unmistakable.) Where the tone isn’t tongue-in-cheek—and that’s most of the book—we have no reason to doubt what we’re being told.

That sense of authenticity only deepens with Hendrix’s piece, which Spratford describes as “a dark story about his father, someone [he] does not often write about.” It’s the first in a section of essays about “very real trauma,” by authors whom she thanks for “shar[ing] their difficult personal stories.” Her language is familiar, and it carries a quiet directive for how to read what comes next—we’ve all been taught (rightly so) to believe victims, and we’re primed to extend that acceptance to the following accounts. By invoking trauma narrative—a mode with a strong whiff of the sacrosanct—she’s telling us, in so many words, that these writers are baring their souls, and only the most cynical jerk would doubt them.

Yet Hendrix undermines the truth claims of the trauma narrative. After presenting pages of damning evidence against his father—stories that, taken together, make a convincing case he’s a serial murderer—he ends by suggesting that maybe we shouldn’t believe him. He places his essay within a long tradition of found-media horror, from The Castle of Otranto to The Blair Witch Project—stories that “clai[m] to be true” and “make you wonder if they really happened.” But while those works preserve a distance between the artist and the art—Horace Walpole isn’t a character in the Italian manuscript he pretends to find—Hendrix collapses that gap. He uses his own name and his father’s, preserving many of the real details of his father’s life: both within the text and outside of it, Grady Hendrix Sr. was a South Carolina cardiologist who died in 2023. What he’s written isn’t memoir, as Spratford prepares us to expect, or found fiction. Instead, it’s autofiction.

He isn’t the first writer to meld genre and autobiographical elements. In Chasing the Boogeyman (2021), Richard Chizmar imports the serial-killer trope into what is largely an autobiographical narrative, while in The Shards (2023), Bret Easton Ellis explores a similar combination, though in a more self-conscious, metafictional mode. Neither of these authors, however, accuse a real person of fictional crimes the way Hendrix does (assuming, of course, that the crimes are fictional). It’s one thing to invent a character and imagine all the horrible acts he’s committed, and it’s another to pin those inventions on your own father. Imagine the awkwardness of a family reunion after that. Fantastical or not, an accusation of serial murder would be enough to tarnish anyone’s reputation, and Grady Hendrix Sr. is no longer alive to defend himself. In other words, there could be collateral damage from this literary exercise and, more than the novels of Chizmar and Ellis, Hendrix’s essay makes those stakes plain. By implicating his father, he foregrounds just how ethically fraught horror autofiction can be.

Spratford might say the union of horror and autofiction is productive. While it’s true she frames the essays in Hendrix’s section as grounded in lived experience, she also says that they “deal with trauma and how horror help[s] to process it.” The word “process” could easily clear the way for metaphorical transformation. It could—and almost certainly does—mean that Hendrix is using the serial-killer trope not literally but symbolically, as a way to dramatize a relationship that’s emotionally difficult, though not necessarily violent or criminal. He suggests as much, toying with the reality status of a child’s severed arm he may (or may not) have found in his father’s freezer: “Maybe that arm in the freezer stands for some other secret my dad kept that I could sense the shape of but never quite pin down.” If that’s what he’s doing, then I’d say it’s a grossly disproportionate response. The threat of the metaphor being literalized is too great: if even one person thinks the arm is real (or wonders if it might be) that’s enough to distort his legacy and the memories of those who knew him.

Using the serial-killer trope as a grammar for articulating emotional difficulty also threatens to trivialize depictions of actual violence. In the piece immediately following Hendrix’s, Cynthia Pelayo recounts her nightmarish childhood and the abuse she endured at her mother’s hands. When a genuine trauma narrative like this appears beside a story structured around one of horror’s most sensational elements, does it risk making them ontologically indistinguishable? I don’t know, but there’s something distinctly uncomfortable about their adjacency.

Making readers uncomfortable seems to be the point of Hendrix’s project. His essay is designed to leave us with no safe place to stand. If we believe what he’s saying, then he’s been sitting on evidence of possible crimes, and there are real families out there suffering as a consequence of his timidity. No one wants to think of him in this light—he’s a hugely popular figure in horror. Yet if we don’t believe him—if we think it’s an experiment in horror autofiction (I raise my hand here)—then he’s defaming his dead father for an artistic effect. Also not nice. “‘Maybe,’” he writes, “is the scariest word in horror.” That’s probably true, and every genre writer should strive to frighten their audience, but is it worth dragging the name of someone close to you? The autofiction reading also means that we’re dismissing a story framed as a recollection of real trauma—essentially saying, “Sorry, Grady, your pain is a sham”—and no one wants to be that insensitive jerk. It’s a no-win scenario. Or, to use a horror trope, maybe it’s like a cursed text, damaging to both its author and reader.

In the introduction to Why I Love Horror, Spratford writes that “‘Why’ is the word to which I have dedicated my entire professional life.” She’s interested not so much in what books people like but in why they like them—what do their preferred narratives do, how do they do it, and why is that appealing? I think “why” is a good word to end on. Pushing beyond what Chizmar and Ellis have done, Hendrix shows us what horror autofiction can be. It’s unsettling and not in a good way. Which leads to the question: Why choose to tell a story in this mode? What’s gained and what’s lost? It’s worth thinking about because, if Hendrix’s essay is influential—and something tells me it might be—we could be in for a lot more ontologically explosive writing: works that suspend dangerous accusations in the realm of “maybe.”